No genre is more ripe for gothicizing than memoir. And in memoir, the gothic can take new forms in ways that reinvent a centuries-old genre. All of the ways in which memoir has the potential to be unsettling are heightened by the use of gothic standbys. It’s a retelling of an experience that feels at once uncanny and uncomfortably familiar to the reader. Machado has the guts and the chops to embrace the fundamental eeriness of her project, and thus invent something new. And yet, for whatever reason, most memoirs not only ignore but resist the innate gothicness of memory instead, they provide an artificially neat story, with no significant hauntings. These are all characteristics of gothic literature, the joys found in reading The Castle of Otranto, the fear waiting for us in Jane Eyre’s red room.

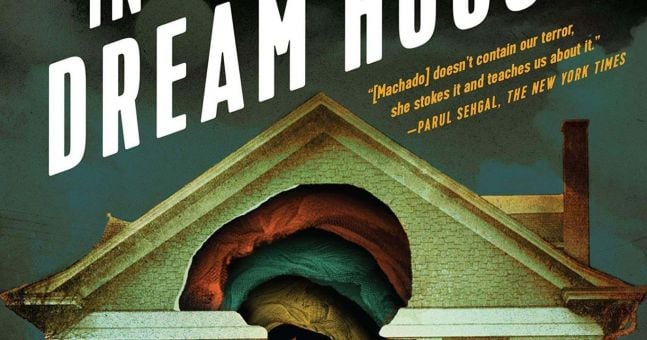

The point in a memoir at which we confront the worst parts of our memory is the ultimate descent: into trauma, into the bottom floors of our minds, into madness. To write about yourself is to double yourself, and looking back at your own life with present-you eyes is definitely uncanny. Surely, no genre is more ripe for gothicizing than the memoir. In Dream House, with its doppelgängers, hauntings and descents into trauma, Machado shows us that there is nothing more gothic than our own memory. We see the dream house as soap opera, folk tale, self-help book and, running throughout always, the gothic.

It picks up tropes, motifs and imagery and mixes and matches with joy.

Dream House takes this to a delightful extreme. Genre is Machado’s sandbox her short story collection, Her Body and Other Parties, troubles genre as often as it indulges in it, cherry picking from science fiction, horror and apocalyptic fiction. This small scene is one glimpse into how In the Dream House is not only a memoir but a masterclass in what genre can do.

And there, at the end of this scene, we have the Dream House, which breathes and terrifies and haunts throughout the memoir. This othering works because that’s how memory works we look back in time to see ourselves talking and acting but we’re powerless to stop it. The construction and style of playwriting is the perfect way to show what is so hard to describe: that trauma objectifies us in the strangest ways, that we can feel like figures moved around on stage by something unseen. This moment, setting the tone in its quiet terror, is an example of what makes Machado’s memoir so extraordinary.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)